Member LoginDividend CushionValue Trap |

Midstreams Going C-Corp, Should SEC Disallow the Measure Distributable Cash Flow?

publication date: Sep 18, 2018

|

author/source: Brian Nelson, CFA

Key Takeaways It’s important to differentiate the concept of enterprise free cash flow valuation and the idea of capital-market dependence. The uncertainty of the MLP business model remains, as it is clear operators are shunning the MLP business model preferring C-Corps instead. According to work from Global X Funds, now 40% of the energy infrastructure market cap consists of C-Corps, up considerably from just 15% at the end of 2014. Though many simplifications have come with implied distribution cuts, the primary reason for the rise in C-Corps across the midstream space has been the rationalizing of excess MLP valuations to enterprise free cash flow assessments. We encourage the SEC to consider disallowing the use of distributable cash flow, as it is confusing to investors. ---------- By Brian Nelson, CFA I think one of the more inspirational people in finance is Vanguard’s Jack Bogle. His story about what he had to overcome to explain to the investment community the benefits of index funds is a great one. When Bogle launched the first index fund decades ago, it could probably be described as nothing short of a failure, at least in today’s terms. Index funds, at the time, were called un-American, brokers and even Fidelity’s Chairman Edward C. Johnson III argued that nobody would want just “average returns,” and Vanguard in its early days didn’t even have enough money to invest in all the stocks of the S&P 500 Index in their exact proportions. The initial index fund on the S&P 500 Index held just 280 stocks. But that didn’t stop Jack Bogle. The old guard is fierce to defeat any new idea because the status quo is so valuable to it. Creative destruction is often only welcomed when the incumbent is doing the innovation, as new ideas, particularly in the field of finance, face tremendous opposition from those that are resistant to change. “Bogle’s folly” (i.e. the index fund) is now arguably among the most successful product idea launches in the history of the markets, with indexed assets accounting for ~30-40% of all fund assets today. In corporate finance, the challenge for others to embrace new ideas is no different. Those that were in the finance business for 30 or 40 years or longer in the 1970s simply couldn’t believe that such a product like an index fund would be successful, and this resistance to new ideas has been a staple to incumbents that have grown comfortable with the status quo, as for many years the lack of change made them wealthy. Wall Street is mighty, but the skeptics can be proven wrong, and Jack Bogle is but one instance. We’ve been commenting on master limited partnerships (MLPs) for as long as I can remember at Valuentum. Depending on an MLP’s price, we can be either bullish or bearish on their investment opportunities, and we change our mind as a result. We believe that valuation should be the key determinant in assessing a company’s investment merits. The question “What is a company worth?” should be the key question in anyone’s thesis. We can’t expect our readers to have read all our work on MLPs during the past several years, which have spanned Seeking Alpha, our website, Tumblr and syndication providers including Barron’s and even others we may not know about, but there is one thing that cuts through it all: enterprise discounted cash flow valuation. Valuing a company on a free-cash-flow-to-the-firm basis is as accepted method of valuation as any that I know. I would argue that it is even the standard by which any other valuation process is measured against. In mid-2015, when we presented the idea that midstream equities should be valued the same way as any other company, the opposition to this very basic idea was tremendous. All companies generate operating cash flow and all companies have growth and maintenance capital spending, and capital raised in the marketplace is still shareholder capital regardless of the business model attached to it. Enterprise free cash flow valuation is a universal concept. Most of the midstream MLPs in mid-2015, in our view, were being valued on the basis of distributable cash flow, which is merely a proxy for their distribution (yield), and many had been systematically assessed on a price-to-distributable cash flow (P/DCF) basis or dividend discount model on artificially-elevated payouts. Distributable cash flow is not to be confused with discounted cash flow, though both go by the acronym DCF. The marketplace, in applying distributed cash flow or distribution analysis, was ignoring the concept that growth capital associated with driving future distributable cash flow is also shareholder capital. Said differently, in the valuation context, MLPs were getting a free pass on new equity/debt issuance, and only through an enterprise free cash flow model could such a dynamic be exposed. It’s important to differentiate the concept of enterprise free cash flow valuation, as in the case of our view that most midstream MLPs were overvalued in mid-2015 (their prices were trading above what we thought was fair value), and the idea of capital-market dependence (their operating cash flow does not cover all capital spending and all distributions). During the Financial Crisis of late last decade, “10 Years Since the Fallout,” one of the key lessons I learned was that the risk of capital-market dependence can be a wrecking ball to equity prices. When times get tough, the bottom simply falls out for those equities requiring new capital, and this fallout in capital-market dependent entities is what we got ahead of prior to the collapse in MLPs. Energy resource prices had been plummeting in 2015, and while others were saying that midstream equities were immune to such price movements due to their volume-based contracts and other defenses, we had argued that the health of a midstream entity’s customer base matters and therefore makes midstream equities significantly more tied to energy resource prices than what others thought at the time. Said differently, in the event credit market conditions were to deteriorate even further as a result of reduced credit quality across the energy space, MLP equity prices would get walloped… and they did, and we were right. But it’s important to understand that MLP prices, in their fallout, have merely adjusted from systematic overvaluation (on the basis of distributable cash flow and the dividend discount model) to fair valuation with respect to enterprise free cash flow.

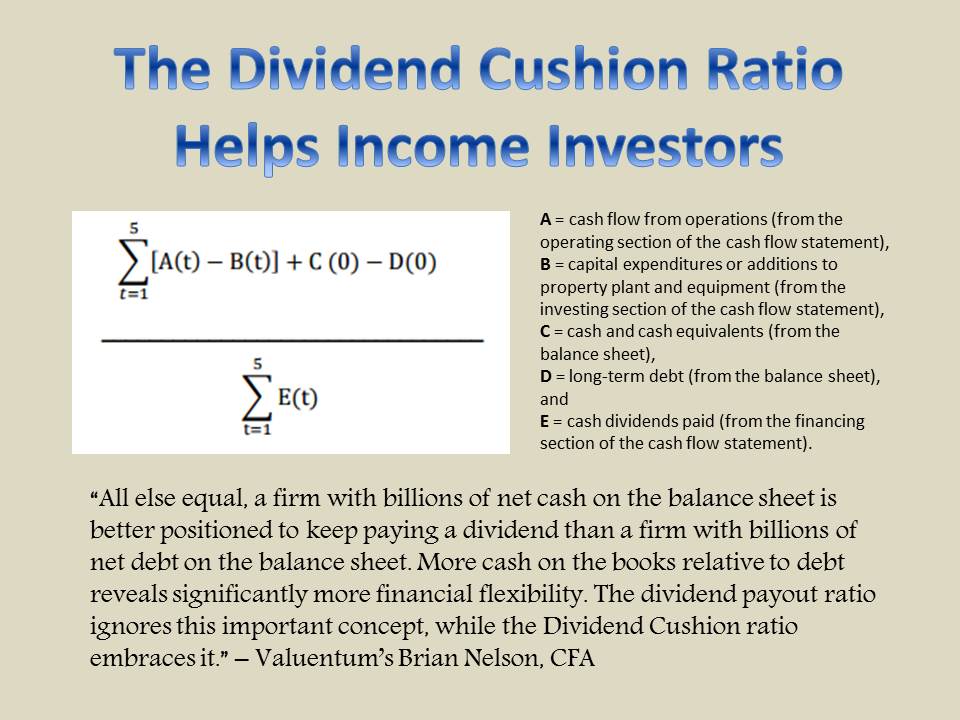

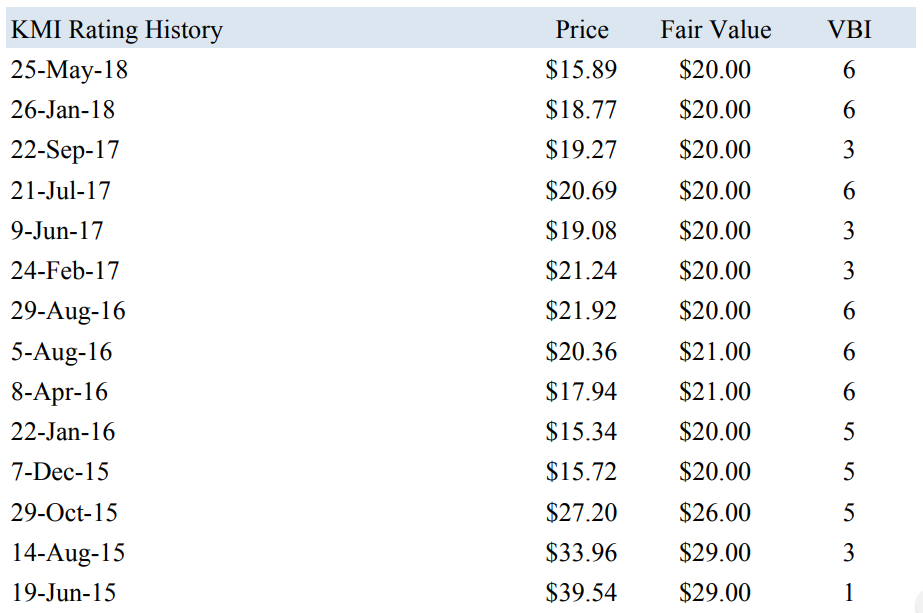

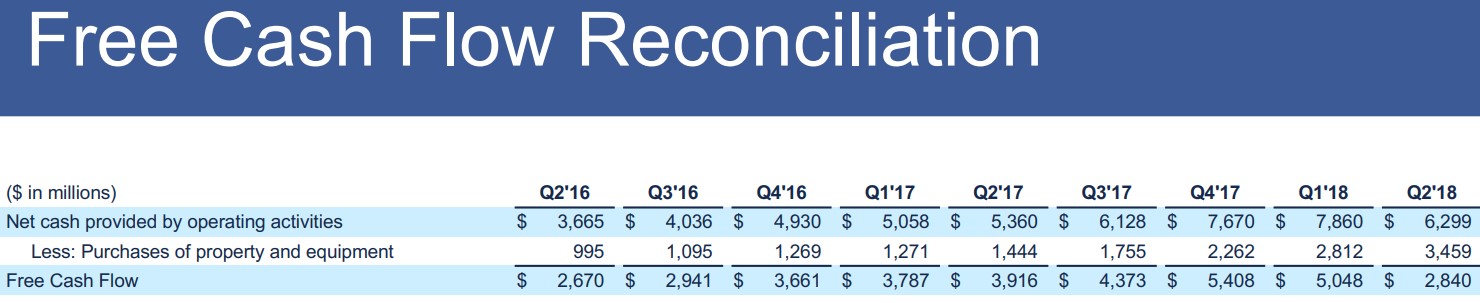

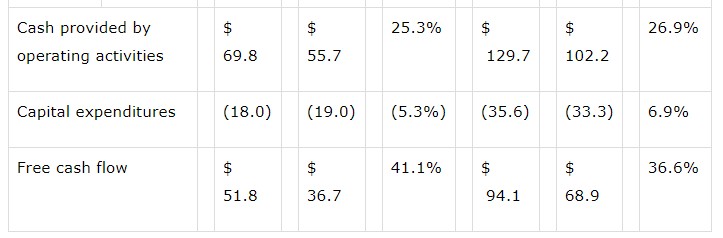

Image Source: Valuentum For example, when we made our call on Kinder Morgan (KMI) in mid-2015, we had valued the shares at $29 each, and the company registered a 1 on the Valuentum Buying Index, one of the worst ratings (as shown in the image above). Shares converged to our fair value estimate later in the year, and we’ve held the line with our views on Kinder Morgan’s intrinsic value being ~$20 per share for nearly 3 years now. What we believe that we witnessed in Kinder Morgan was a systematic correction in the market’s valuation of the company. MLPs reacted the same way, converging to valuations that captured the real cost of growth capital spending. When we speak of enterprise discounted cash flow valuation, this dynamic of overvalued-versus-undervalued is what we’re talking about. Additionally, Kinder Morgan cut its dividend in late 2015. There were myriad factors that drove the dividend cut, but to us, getting ahead of the announcement rested primarily in free cash flow analysis, which while connected, remains distinct from enterprise free cash flow valuation (also a key component of our theses), the method to arrive at an intrinsic value. Where enterprise free cash flow analysis focuses on generating a fair value estimate for shares, capital-market dependence analysis focuses on evaluating how dependent a company is on external capital to keep funding its business model. We generally evaluate market dependence in assessing whether operating cash flow (from the cash flow statement) covers both capital spending (both growth and maintenance) and distributions/dividends paid. When it came to Kinder Morgan and most MLPs in mid-2015, they were considerably capital-market dependent at a time when the energy complex was starting to feel the pain from falling energy resource prices. Not only were they exposed to deteriorating credit conditions in this regard, but their equity prices were also significantly overvalued on the basis of a tried-and-true enterprise discounted cash flow framework, which considers the concept that growth capital is shareholder capital and the timing of such capital deployment (outflows) matters. It was a perfect storm that led to the collapse of Kinder Morgan and MLPs. How did we get ahead of this, and why was our thesis so unique? For starters, we apply an enterprise free cash flow model systematically across our coverage universe, so we think we have a better chance of identifying market outliers across industries and sectors than others focusing purely on one industry or a sector, or just a handful of them. Second, the lessons from the Financial Crisis with respect to banks were clear. Stocks that were capital-market dependent during the Financial Crisis were punished, and we believed that with energy resource prices falling, putting into question the health of independents, which were customers of MLPs, the writing was on the wall for a big fallout. Since Barron’s prominently published our work on Kinder Morgan and MLPs in mid-2015, more than 60 MLPs have cut their distributions and many of them have rolled up or simplified their business operations. The uncertainty of the MLP business model remains, as it is clear operators are shunning the MLP business model preferring C-Corps instead. In August 2014, Kinder Morgan set the trend in MLP rollups, and the number of rollups have only continued, “Master Limited Partnership Simplications on the Rise,” including ArchRock Partners (APLP), Tallgrass (TEP), Williams (WPZ), Spectra (SEP), and Enbridge (EEP). According to work from Global X Funds, now 40% of the energy infrastructure market cap consists of C-Corps, up considerably from just 15% at the end of 2014. Will every current MLP convert to a C-Corp? It’s possible. But as with anything, there will always be late movers, and many MLPs are still watching to see if the C-Corp conversions will be successful in generating better reception from the market community. Everything takes time, and our time horizon on our call is long term. What is telling, however, is that many new issues for midstream assets have chosen the C-Corp route. Diamondback Energy (FANG) announced an IPO for their midstream entity, Rattler Midstream (RTLR) that, while structured as an MLP, will be taxed as a C-Corp. Apache Corp (APA) and Kayne Anderson (KYN) announced that they are creating a brand new C-Corp entity Atlus Midstream, according to Global X. On August 24, Enbridge (ENB) announced that it would buy Spectra Energy Partners. This followed the Energy Transfer Equity (ETE) and Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) tie up, "ETE-ETP Rollup and Implied Distribution Cut." Consolidations continue to slowly eliminate the MLP model. Though many simplifications have come with implied distribution cuts, the primary reason for the rise in C-Corps across the midstream space has been the rationalizing of excess MLP valuations to enterprise free cash flow assessments, eliminating distributable cash-flow (yield) based pricing, something we warned about in mid-2015 when we stated that growth capital was not being properly accounted for within the MLP valuation construct: In summarizing the reasoning behind the use of the C-Corp structure, Kevin McCarthy, an executive at Kayne Anderson stated, “MLPs are no longer getting a premium valuation compared to C-Corps. There’s been a lot of C-Corp conversions in the space. And we think for this type of asset, the market will place a premium on something that’s a C-Corp rather than something that’s paying out all this cash flow and having to come to the market to fund growth.” In other words, the MLP tax structure is no longer favored in today’s dynamic environment, with preference being given to the more flexible and accessible C-Corp structure. Given the uncertainty that has plagued MLPs over the past few years and how much the business model has changed in such a short period of time, it’s difficult to argue against that thinking. – Source: Global X As summarized above, the story of the demise of the MLP model seems rather simple, in our eyes. From where we stand, the MLP model was used primarily as a financing mechanism that could raise equity for the corporate umbrella at a price that was reflective of a yield-based valuation, or one that is effectively priced on the concept of distributable cash flow (not on an enterprise discounted cash flow basis). Distributable cash flow is an industry specific term that ignores growth capital spending, but includes the net income within the measure that is driven by growth capital spending, "MLP Speak: A Critique of Distributable Cash Flow." This imbalance, in our view, translated into equity unit prices for MLPs of bubble proportions that eventually popped as the energy resource markets began to swoon in late 2015 and early 2016, and funding dried up. Since then, many midstream companies have become more transparent, better explaining their capital-market dependency to shareholders. For example, in the ENB/SEP press release from August 24: "MLPs are dependent on consistent access to the capital markets at a reasonable cost of capital to grow their distributions." It seems there should be no further doubt that MLPs are funding their distributions in part from the external capital markets. Generally speaking (and absent the concept of negative yielding debt on corporates), the lowest cost form of capital is generated from internal funds (operating cash flow), and such funds are allocated to the highest-return projects (growth capital spending). Once operating cash flow is exhausted from all capital spending, including growth-related endeavors, external capital issuance, which is higher cost funding, is then allocated as support for the distributions of MLPs. The concept of traditional free cash flow is a well-understood measure. It is generally defined as cash flow from operations less all capital spending. It’s important to note that when it comes to valuation processes, all companies have maintenance and growth capital spending, and even some ultra-efficient technology companies could have lower maintenance spending profiles than midstream pipeline entities (so the maintenance-versus-growth capital spending ratio varies across sectors, but it is not different for MLPs in the eyes of valuation). There are myriad examples of companies that use free cash flow in reporting, as measured by cash from operations less all capital spending, including Facebook (FB) and even research provider Morningstar (MORN).

Image Source: Facebook

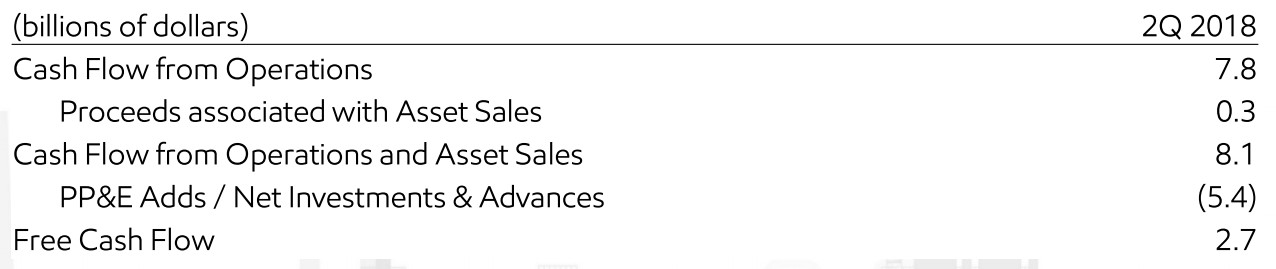

Image Source: Seeking Alpha There are variants of free cash flow representation, too, and while we generally do not like situations where companies deviate from cash flow from operations less all capital spending as the measure of free cash flow in disclosures, the concept of cash flow from operations less all capital spending remains the key relationship in assessing free cash flow. For example, Exxon Mobil (XOM) includes ‘Proceeds associated with Asset Sales’ in the calculation of free cash flow, as shown in the image below, something that we’d prefer not to be in there. Though we have our preferences, the construct is the same in assessing operating cash flow less all capital spending in arriving at free cash flow.

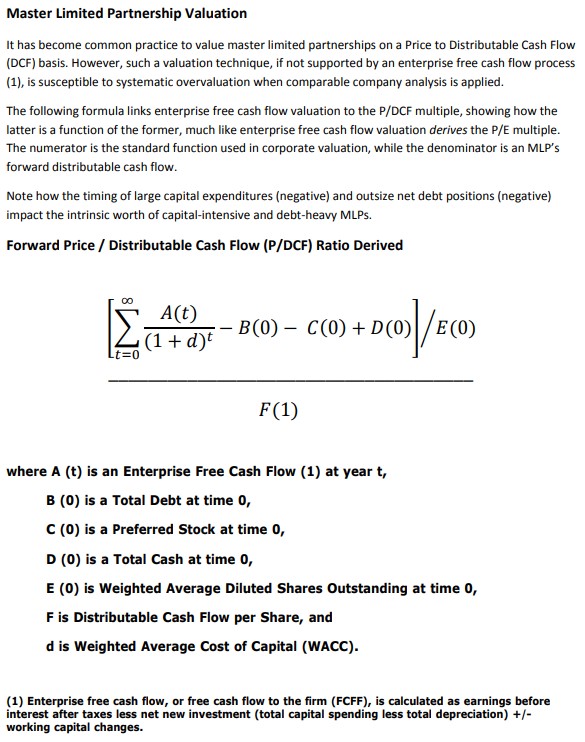

Image Source: Exxon Mobil The SEC, too, has commented specifically on free cash flow, a measure that deducts for all capital spending, not just maintenance capital spending. In the SEC’s May 2016 guidelines for free cash flow, it reads (Question 102.07) in response to a question that defines free cash flow as cash flow from operations…less capital expenditures: “Companies should also avoid inappropriate or potentially misleading inferences about its usefulness. For example, "free cash flow" should not be used in a manner that inappropriately implies that the measure represents the residual cash flow available for discretionary expenditures, since many companies have mandatory debt service requirements or other non-discretionary expenditures that are not deducted from the measure.” The guidelines make a lot of sense to us. However, when we think about the SEC’s guidelines for free cash flow, a punitive metric that deducts for all capital spending, it becomes questionable whether distributable cash flow, because it does not deduct for growth capital spending, is a useful measure at all. After all, the general partner determines a discretionary reserve with respect to distributions, distribution coverage ratios vary quarter-to-quarter and are not fixed at 1, more than 60 MLPs have opted to cut their distributions since we warned about their business models in mid-2015, and many have chosen to pursue business-model simplification initiatives, rolling up subsidiaries and adjusting their payouts along the way. Yet, distributable cash flow continues to set MLP distribution policy, enabling “yield,” which then may drive equity “valuations,” something that we believe contributed to the bubble in early 2015 (see here on how traditional enterprise valuation can be used to value MLPs). Critically, if traditional free cash flow should not be viewed as a measure representing “the residual cash flow available for discretionary expenditures,” including dividend policy (which is discretionary), some may reason that distributable cash flow should probably not be used either to set MLP distribution policy, itself discretionary to a large degree. We applaud the SEC’s move to caution companies on how they present free cash flow, and we’re hoping that we may eventually see a systematic measure of free cash flow as a mandatory release for all companies--hopefully one as simple and straightforward as cash flow from operations less all gross capital spending (companies sometimes like to use net capital spending). The transparency and consistency that this one move would make across the financial markets would be phenomenal, and we hope one day we will see this. One thing is clear though: if free cash flow, which deducts for all growth spending, is not a good measure of residual cash flow, distributable cash flow should probably not be allowed at all. Why now does enterprise free cash flow valuation make sense for MLPs? There are a number of ways to account for business performance across various business structures, whether an entity is a corporate, REIT, or master limited partnership, but cash flow will always be cash flow. In finance (and in valuation), a business, for example, cannot be worth more or less than the present value of its future enterprise free cash flows, adjusted for its net balance sheet (a net debt or a net cash position), as well as any other “hidden” factors (e.g. an overfunded pension)--no matter if the entity is structured as a corporate, a real estate investment trust (REIT) or a master limited partnership. The prices of these entities may become disconnected from their intrinsic value, if for example, "yield-based pricing" (systematic valuation on distributable cash flow) is pursued in an ultra-low interest rate environment, but value will always be value, distinct from price. A dollar of free cash flow generated by a retailer is a dollar generated by a software company is a dollar generated by a midstream entity. The present value of dollars coming in versus dollars going out forms the basis of any valuation context. As mentioned previously, every company has both growth and maintenance spending, and the drivers behind the composition of any entity’s value are the same, differentiated only with respect to magnitude and duration. In this respect, all midstream MLPs are similar, even if the magnitude and duration behind the composition of their value drivers are different. Said plainly, many pipeline companies may have relatively low maintenance capital spending, all else equal, but so do many software companies and other asset light entities, too. Many capital-light operations do not have tremendous growth capital spending, as fixed cost investment is not a core driver behind the earnings stream, but midstream entities do. The midstream space almost encourages analytical thinking on a project-by-project basis, which is great with respect to NPV (net present value) considerations, but all projects roll up into a cumulative forward trajectory of net free cash flow (cash flow from operations less all capital spending) for each and every entity and form the basis of a value estimate for each and every entity. That an industry has designated the term distributable cash flow to mean one thing does not change the theoretical view that, hypothetically, distributable cash flow, in a more encompassing non-MLP-specific context, could even be further up the income statement, as in revenue (a rather extreme hypothetical, but one that illustrates the subjective nature of the industry's term). As by definition, the industry's measure of distributable cash flow backs out growth capital spending, but doing so may be no logically different in substance than revenue, for example, being perhaps an even more aggressive form of "distributable cash flow," if one backs out all costs. In both cases, any traditional free cash flow shortfalls, as measured by cash flow from operations less all capital spending, would be made up by floating new debt or equity to keep paying an outsize distribution/dividend, as is already the case with respect to the master limited partnership model, in our view. Cash flow from operations less all capital spending is often less than cash dividends paid each year for MLPs, and the shortfall is made up in the financing section of the cash flow statement as new debt or new equity. We've used the rather extreme concept of labeling 'revenue' as some unrealistic measure of distributable cash flow to illustrate a point. Not only must growth capital spending and costs be considered in the valuation context, but it becomes clear that there is a tremendous amount of subjectivity involved in the industry's term, distributable cash flow (especially with respect to capital market access). In the eyes of an enterprise free cash flow model (FCFF, free cash flow to the firm), however, business entities of all types are treated similarly, and the enterprise free cash flow generated by the business, in aggregate, is considered, on a net basis (inclusive of outflows related to growth spending). The timing of cash flows matter in the enterprise free cash flow process, and so does the balance sheet (net debt is not a good thing). For those focused on value-contributions of each individual project of a pipeline operator as only being incremental, what may be helpful is to consider an MLP as one big project, one big NPV calculation, and therefore, one enterprise free cash flow model, where the timing of net enterprise cash flows matter, in aggregate. In the image below, we show the link between the industry-specific metric distributable cash flow and the basic construct of an enterprise free cash flow model.

Image Source: Valuentum The numerator is a short-form construct of an enterprise free cash flow model, which takes the present value of a company's earnings before interest, after taxes, less net new investment (or enterprise free cash flow) and divides that by units outstanding. The denominator is the industry specific term distributable cash flow for next year. The formula above therefore derives the value that should be placed on the business via the enterprise free cash flow construct, and then this value estimate helps to inform what multiple of forward expected distributable cash flow should be applied to units. In short, the enterprise free cash flow derives the distributable cash flow multiple that should be placed on the business, which differs from the price-observed distributable cash flow multiple that is taken by dividing a unit's price by its future distributable cash flow, for example. The reason why using an enterprise free cash flow model in valuation is so important for MLPs is that, if one applies only a distributable cash-flow relative analysis or pursues "yield-based" pricing considerations, one is opening the door to systematic overvaluation tendencies, as which occurred during the middle of 2015 when we made our call. Conclusion From where we stand, the MLP-specific term distributable cash flow is an arbitrary one, and all entities, whether they are a corporate, REIT, or MLP have both growth and maintenance spending, the magnitude the only difference. In an extreme case to illustrate the point of how subjective distributable cash flow as a metric is, revenue could even be considered a form of distributable cash flow, with any cash shortfalls relative to any dividend/distribution made up by external capital market issuance. An enterprise discounted cash flow model derives the price-to-distributable cash flow metric that should be placed on each MLP’s units, and systematic mispricings could occur if investors solely rely on relative distributable cash-flow analysis or “yield-based” pricing considerations. We encourage the SEC to consider disallowing the use of distributable cash flow, as it is confusing to investors. When we released these ideas in mid-2015 more broadly, we didn’t expect everybody to agree with us, similar to what Jack Bogle encountered when he first introduced the index fund to the investment community. Energy investors have been using distributable cash flow arguably for decades, but enterprise free cash flow valuation remains a tried-and-true method that considers all the cash inflows and outflows of the business, unlike distributable cash flow (and yield) which is rather arbitrary and excludes key growth capital spending. Within an enterprise discounted cash flow valuation model, the dividend is a symptom not a driver of value, and by extension, so is distributable cash flow and yield, both symptoms of value (not drivers). We continue to believe that investors should cast a cautious eye on the MLP business model, if only because of its considerable capital-market dependency risk, which could pose challenges in the event of tightening external capital market conditions. Pipelines - Oil & Gas: BPL, BWP, DCP, ENB, EPD, ETP, GMLP, HEP, KMI, MMP, NS, PAA, SEP, WES Tickerized for holdings in the Alerian MLP ETF (AMLP). ----- Valuentum members have access to our 16-page stock reports, Valuentum Buying Index ratings, Dividend Cushion ratios, fair value estimates and ranges, dividend reports and more. Not a member? Subscribe today. The first 14 days are free. Brian Nelson does not own shares in any of the securities mentioned above. Some of the companies written about in this article may be included in Valuentum's simulated newsletter portfolios. Contact Valuentum for more information about its editorial policies. |

1 Comments Posted Leave a comment