Member LoginDividend CushionValue Trap |

Empirical Support for Porter’s “Gospel,” Plus Comments on the “Head Fake” Rotation

publication date: Sep 23, 2019

|

author/source: Valuentum Analysts

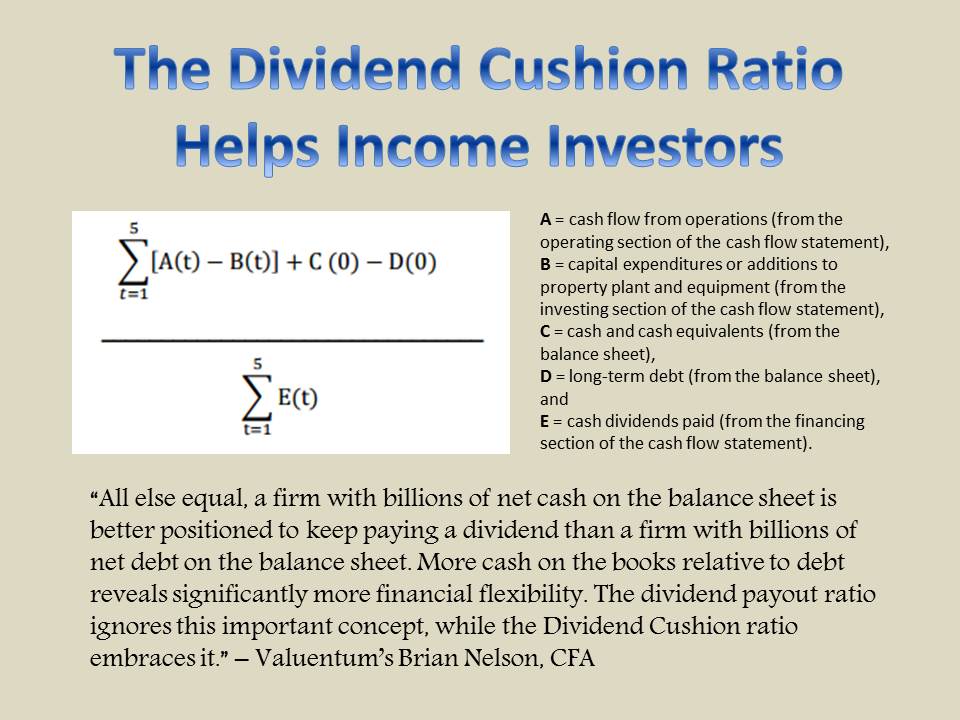

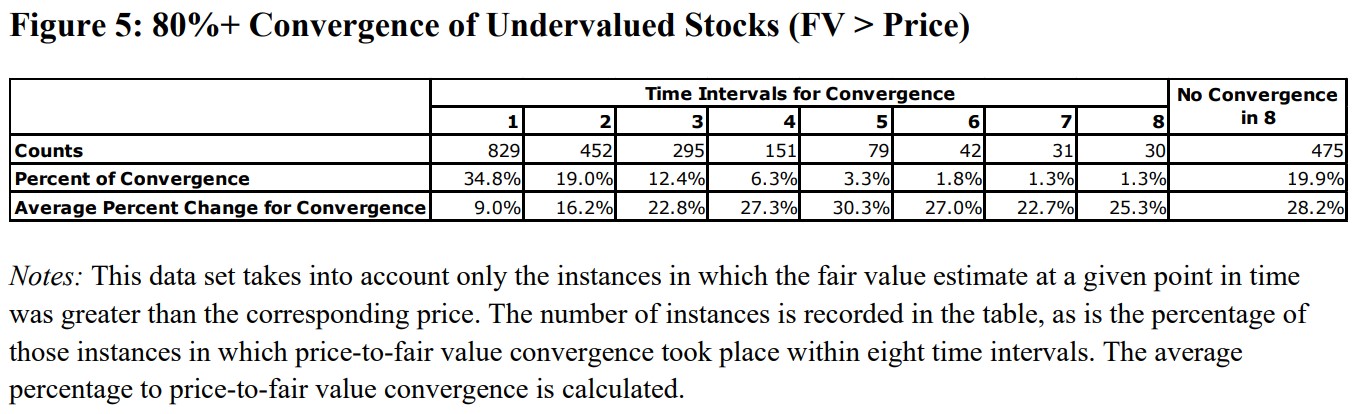

“Let’s be very clear: There is strong empirical quantitative evidence that the price-to-fair value equation (“factor”) is predictive of returns, which is what matters for value investors, and in Morningstar’s case, the moat assessment is just part of that overarching conclusion (fair value estimate). Researchers continue to attack the moat “factor” on grounds that don’t make any sense, in my view, and are cherry-picking parameters to assess value investing.” – Brian Nelson, CFA Note tickerized for holdings in the DIA. In the latest installment of Valuentum’s Economic Roundtable, the team talks more about economic moats (this time, in the context of competitive strategy, in the lens of famous academic Michael Porter and his well-renown 5 Forces model), as well as why the recent rotation from “growth” into “value” may not last. We have lots to say, and let’s get things started with the following prompt from the Institutional Investor, The Gospel According to Michael Porter: Value investing used to be about betting on the underdog — finding the down-and-out losers and gambling that they might have one more fight left in them. Today’s value investors have a new gospel: Harvard Business School professor Michael Porter’s Competitive Strategy. Porter’s theory is that power leads to profits. The wider the moat, the greater the market share, the greater a company’s ability to squeeze profits from competitors, suppliers, and customers. Porter tells a modern parable of the Five Forces — the professor’s signature analysis framework — that gave Goliath a sustainable competitive advantage over David. But the founder of value investing, Benjamin Graham, was a poor Jewish immigrant who made his name betting on the Davids of the stock market. The legendary Graham believed that investors could make money by betting against consensus when that consensus went against the numbers. There is perhaps no greater gap between consensus and numbers today than in the application of Porter’s competitive strategy to investing. Unlike Graham’s quantitative methodology, which has endlessly been empirically proven, Porter’s competitive strategy principles have no empirical foundation. There is simply no evidence — not a single quantitative study — to support his conclusions. Brian Nelson: Boy, where do you begin? Okay, well, there are many types of value investors. For starters, as I write in Value Trap, Valuentum is a subset of value investors, and we don’t like to bet against the market. We like to bet on undervalued ideas that are going up, or ideas that both the market and our team agree are undervalued (we view an appreciating stock price as the market thinking shares should be valued higher). We like betting with the market, not against it. So, the idea that value investors only like “down-and-out-losers” couldn’t be further from reality. Now onto the second assumption: that value investors only focus on competitive strategy, or Porter’s 5 Forces, more commonly found in the frameworks of moat analysis. As we talked extensively about in our latest Economic Commentary, “Quant Quake, “Quac-cidental Correlation,” and Economic Moats,” Porter’s 5 Forces analysis, or moat analysis, is only one part of value investing; moat analysis helps in assessing value, but it is not the conclusion, the fair value estimate. The most important part of value investing is buying stocks below an informed estimate of their intrinsic value, or a price-to-fair value estimate ratio far below 1. The moat may signal a company is a strong economic value-generator, but strong value-creation says little about whether the company may be a bargain. Whether a company is a bargain or value stock is what the price-to-fair value ratio reveals. Quite simply, a wide moat can be overvalued, a no moat can be undervalued, much like a high P/E stock can be undervalued or a low P/E stock can be overvalued. Only through a comparison of a company’s price and intrinsic value can the merits of the investment opportunity be considered. In assessing value investing, the P/FV is the ratio to test, not Porter’s 5 Forces or the moat “factor.” As I write in Value Trap, there are numerous studies from Morningstar and Valuentum that show the predictive power of fair value estimates. In the October/November 2013 edition of Morningstar Advisor magazine, for example, Morningstar noted that the fair value estimate “has significant forecasting capability even when other independent variables such as size, book-to-market ratio, volatility, and momentum are controlled for. The t-stat is 2.83, which indicates that the predictive power is statistically significant at the 1% level.” A huge shout-out to the authors of the piece. It offers excellent quantitative work showing how Porter’s 5 Forces or moat analysis can inform the fair value estimate, which is what competitive analysis is intended to do (help enhance the likelihood of risk-adjusted price-to-fair-value convergence). Even though the moat can be viewed as a “factor,” much like size or book-to-market or momentum, and that’s how it is being presented quantitatively, when it comes to evaluating the merits of value investing, however, only studies that consider a comparison of a company’s price with that of its estimated intrinsic value are relevant. The moat is just one part of the value equation. Valuentum has also run studies on its own fair value estimates. Where the Morningstar study compares the performance of undervalued versus overvalued stocks, a recent Valuentum study from 2017 compared the likelihood of price-to-fair value convergence, itself. In our paper, “How Well Do Enterprise-Cash-Flow-Derived Fair Value Estimates Predict Future Stock Prices (pdf),” in the bucket of undervalued stocks in the study, more than 80% of fair value estimates resulted in price-to-fair value convergence (closing ~30% price gaps over a future 3-year period, on average). Furthermore, roughly 40% of overvalued stocks converged to their fair value estimates in the study, despite the time of the data in the study occurring during one of the strongest bull markets in history. [In all, ~59% of stocks in the study converged to their estimated intrinsic value estimates.]

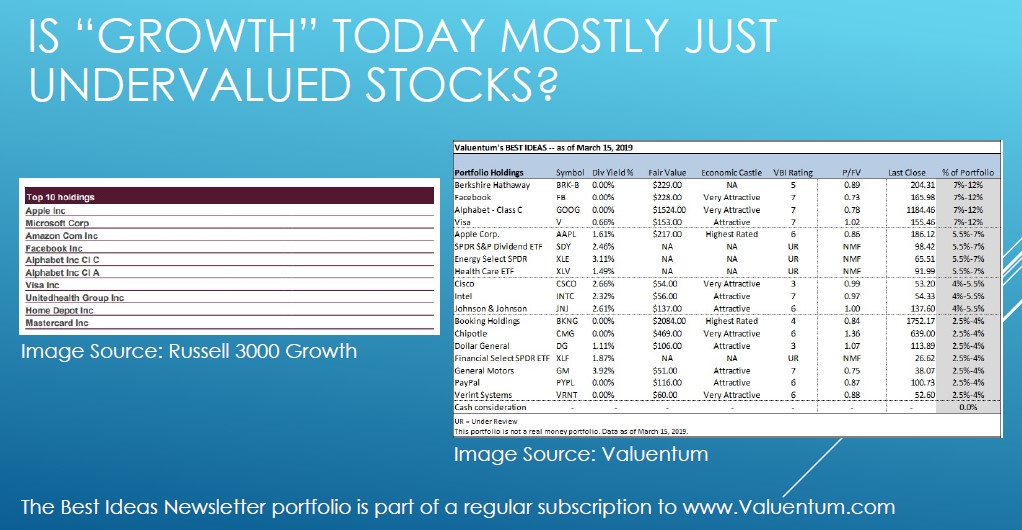

Let’s be very clear: There is strong empirical quantitative evidence that the price-to-fair value equation (“factor”) is predictive of returns, which is what matters for value investors, and in Morningstar’s case, the moat assessment is just part of that overarching conclusion (fair value estimate). Researchers continue to attack the moat “factor” on grounds that don’t make any sense, in my view, and are cherry-picking parameters to assess value investing. Furthermore, the article that was block quoted above credits the University of Chicago school for simply backtesting that “the best-returning stocks are the small value companies like those Graham invested in…” Walk forward studies regarding these same parameters, however, have indicated a much less-clear picture. In fact, the book-to-market ratio has failed more in live testing than in all of the backtest that made it infamous, and researchers such as AQR’s Cliff Asness suggest that there’s really not a size effect “factor”. It’s quite the conundrum that this article reveals. Many try to discredit moat investing by looking at it solely as one “factor,” but it is just one part of arriving at a fair value estimate, and the fair value estimate is most important. Further, critics of Porter’s 5 Forces suggest that there’s no empirical evidence supporting Porter’s 5 Forces, but there really shouldn’t be because it is the price-to-fair value ratio that’s most important (the emprical support for Porter's 5 Forces is indirectly revealed in the efficacy of the fair value estimate). Such critics point to the Chicago school’s empirical work regarding book-to-market and size, but both of these “factors” just aren’t lining up empirically in walk-forward performance, and this is actually how these quantitative factors should be judged, unlike the moat. The reality is that the price-to-fair value ratio should be the prime value statistical metric to be used in any empirical quantitative value study. I don’t even think the industry is operating under the correct assumptions to even get close to measuring what it is trying to measure when it comes to value investing. I won’t repeat myself too much here, but readers can learn more about what I am talking about in my book Value Trap. The bottom line is that an analyst/investor has to understand competitive strategy (“moats”) to make good financial forecasts, and the analyst/investor needs to make good financial forecasts to arrive at a good fair value estimate, and the analyst/investor needs a good gap (Benjamin Graham called this gap a margin of safety) between a fair value estimate and the share price to identify a value stock, to become a good value investor. This is just the basic value process. Valuentum overlays its own unique value process with the view that there really is no “true” fair value estimate, but rather that the goal of value investing is to properly assess what others think the true intrinsic value estimate should be. We combine the enterprise valuation (FCFF) process, which results in a fair value estimate, with behavioral multiple analysis, and technical/momentum indicators to bolster our view on whether price-to-estimated fair value convergence may occur (on the basis of our subjective fair value estimates; the market eventually must agree with us for us to be right). Quantitative research studying backward-looking ambiguous and realized factors, however, is simply confusing “everybody,” even while most of the widely-accepted empirical research of the past continues to fail, from the CAPM to the three-factor model and beyond. Callum Turcan: This is just a thought and something we did touch on in the past, and that comes down to whether the "moat" factor (thinking about the Morningstar study with respect to moats, not the fair value estimate study referenced above) is being misclassified for smaller companies. For example, smaller SaaS companies might have substantially larger moats than first glance (particularly when those SaaS firms reach a certain velocity), as companies like Inovalon Holdings Inc (INOV) and Avalara (AVLR) have large moats created by the regulatory complexities of the environments they are operating in (on top of these types of firms needing to be based in the US or have a serious US presence, which further limits competition as foreign companies are less likely to jump in, a lot less likely given the regulatory complexities and potential legal penalties when doing things wrong when it comes to healthcare and compliance activities). [INOV and AVLR were recently highlighted in Valuentum's presitigious Exclusive publication. Order here.] Matthew Warren: I think the article misses Porter’s focus when it talks only about large size and market share as being the end all. Small market cap companies with small market share can dominate a niche and score very well on Porter’s 5 Forces. SaaS companies are a great example. I am a believer in the framework as a great tool towards analyzing company moats against the backdrop of industry structure. Over long periods of time, the stock returns should mirror the fundamental performance of the company, barring massive initial overvaluation. I think Brian’s point about Morningstar and Netflix (NFLX) is a great example of where missing an emerging moat on a massive compounder can be a huge error of omission. Missing investing early in Amazon (AMZN) would be a similar story for so many investors. Also, I would argue Buffett’s lower returns in later years are due to the size of Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A, BRK.B), not the fact the he started focusing on moats. If anything, Buffett himself has said he has had to park money in lesser-advantaged companies like utilities due to sheer size. Callum: To your last point Matt, that was a huge reason behind Berkshire Hathaway's desire to help fund Occidental Petroleum's (OXY) recent purchase of Anadarko Petroleum (ex-ticker APC), buying a $10 billion preferred issue from Occidental that came with a generous (relative to what Occidental's long-term bonds were yielding) 8% coupon along with warrants. Before that, there was the large preferred stake Berkshire took in Goldman Sachs (GS) to help Goldman ride out the Great Financial Crisis, which in the end worked out very handsomely for Berkshire. These large and extremely lucrative opportunities only come around so often, when Berkshire can lock in a nice 8% return in a bond-like investment (keeping seniority in mind, of course, during adverse economic conditions) on top of upside via warrants while the ten-year US Treasury is yielding ~2% or less. Matthew: That's true. Size and a huge cash pile definitely gives Berkshire these unique opportunities that usually come up during times of stress. I think Berkshire's size makes it hard for them to buy publicly-traded equities though. Berkshire could take out all of Inovalon, and it wouldn't move the needle. Callum: Oh for sure Matt--the only needle-moving bet for Berkshire when it comes to publicly-traded equities is to put down tens of billions on a large tech or financial company, but that leaves Berkshire few options on what securities to invest in. Instead of finding alpha across all domestic securities, Buffett and Munger are forced to choose between making a $50 billion bet on Apple (AAPL) and Facebook (FB) or further increasing its exposure to financials given the existing Wells Fargo (WFC) stake, as such a large investment in any other publicly traded firm would likely send equity prices up well north of their intrinsic value. Even a company with a market cap of $200 billion could see shares run higher than Berkshire would like, just given its sheer size. I'm 100% with you there. Matthew: Invesco posted the following on its blog, “Be wary of the market leadership rotation (September 12).” Callum: I've only seen notes (like this one from Invesco's Krishna Memani) from investors highlighting how the most recent rotation out of "growth" and into "value" is a head fake. The argument against this being a head fake is that if economic growth stabilizes (due to potential stimulus action in Germany, China managing the slowdown in its economy, and the American consumer remaining strong, among other factors) and interest rates begin to structurally increase, then the justification for hiding out a recession in secular growth plays becomes weaker potentially driving greater investor interest in "value" plays (industrials and other cyclical plays) thus maintaining the rotation. I doubt the outlook for the global economy will change anytime soon as things are still sharply slowing down in developed markets all across the globe. Brian: I generally agree with the takeaway from the piece not to “let the talk of rotation or regime change sway you into making meaningful changes in your portfolio.” While we may have a similar conclusion as Invesco, the reasoning is somewhat different. The recent rotation from “growth” into “value” was backed by rising interest rates and more optimism surrounding the economy. One might expect rising interest rates to hurt long-duration high growth equities as the larger cash flows further into the future are worth less (given the discount mechanism of rates), while global economic growth may not necessarily benefit the secular growers as much as those beholden to the general economic cycle (cash flows of secular growers are less dependent on core growth than cyclicals). That’s why under a scenario of lower rates and lower economic growth, which is what we are generally expecting over the longer haul (relative to the opposite conditions experienced more recently that have driven the “rotation”), high growth equities may continue to win against what is traditionally viewed as their “value” counterparts. The value of the long-duration cash flows of traditional “value” equities aren’t as sensitive to interest rates, and general economic conditions are more impactful to them. The situation that Invesco lays out is rather consistent with the Theory of Universal Valuation, and the takeaway is rather independent of “growth” versus “value” talk, too, as we generally view many of the fast-growing equities on the market today as undervalued, also consistent with the Theory of Universal Valuation. Where some talk “value” versus “growth,” we continue to expect undervalued, growthy portfolio constituents that are revealing strong momentum to do well. Note how many of our best undervalued ideas are “growth” stocks.

Note: This image is from March 2019. There have been changes to the Best Ideas Newsletter portfolio since this time. Matthew: My inclination is that Mr. Memani is right. I think we are heading for slow growth at best or more likely right into a recession in the next 6-18 months. That’s just my best guess and not something that’s investible. If I’m right, the rotation is definitely a head fake. I think the latest Fed cut is a Rorschach test. To me, they are cutting ahead of a recession. Others will hope it’s a mid-cycle “insurance” cut that gives growth a boost. (I don’t think rate cuts will be a meaningful boost to the real economy). Join the conversation. What do you think about Porter’s 5 Forces? Is the “value” versus “growth” discussion getting tired in the field of finance? Here’s what Buffett has to say about value versus growth: But how, you will ask, does one decide what [stocks are] "attractive"? Most analysts feel they must choose between two approaches customarily thought to be in opposition: "value" and "growth,"...We view that as fuzzy thinking...Growth is always a component of value [and] the very term "value investing" is redundant. -- Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway annual report, 1992 |

0 Comments Posted Leave a comment