Member LoginDividend CushionValue Trap |

Case Study: How to Assess Earnings Quality

publication date: May 1, 2023

|

author/source: Brian Nelson, CFA

By Brian Nelson, CFA Let’s first become acquainted with why assessing earnings quality is important. According to the Research Foundation of the CFA Institute:

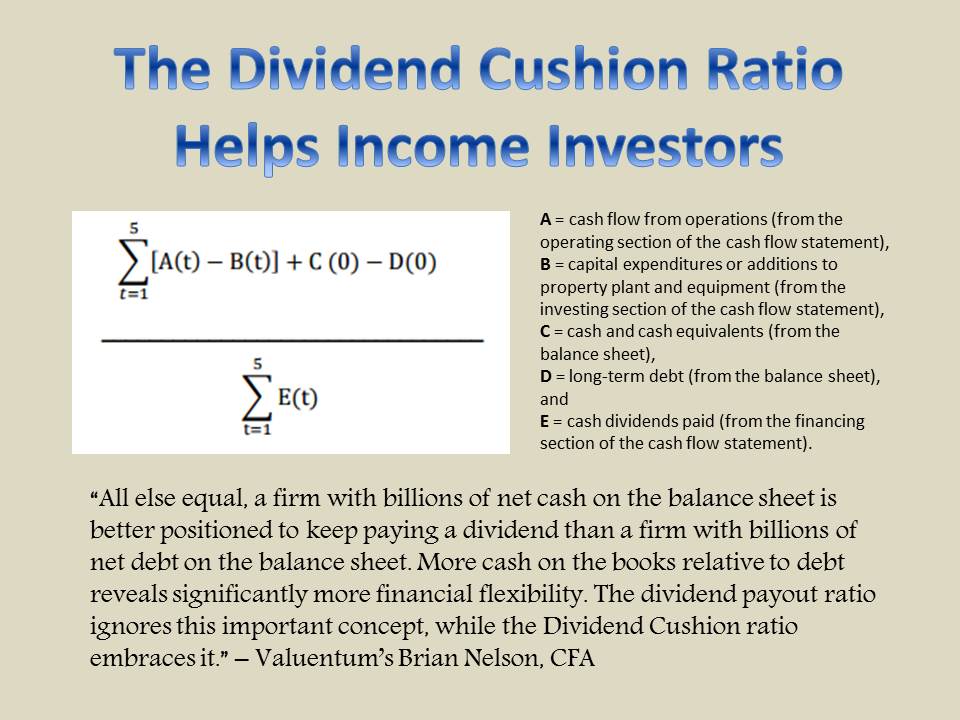

Understanding the quality of earnings is an essential part of processing and interpreting information. A high-quality earnings number will (1) reflect current operating performance, (2) be a good indicator of future operating performance, (3) and fairly annuitize the intrinsic value of the company. At Valuentum, there are five basic areas that we evaluate to assess the quality of a firm’s earnings: a) is the company’s earnings growth driven by higher-quality revenue expansion or lower-quality cost-cutting measures (can the trajectory of earnings be sustained with continued revenue increases because cost-cutting, by definition, is a finite activity?); b) has the company benefited from one-time items and/or an abnormally low tax rate to bolster net income (is the company shifting items from one period to the next?) c) has the company engaged in aggressive share buybacks to bolster earnings per share (is management incentivized based on return on invested capital or accounting earnings per share, the latter not always in the best interests of shareholders?); d) does the company convert 100%+ of its net income into cash flow from operations (are the earnings it generates truly cash earnings or are they more an accounting measure?); e) was there a large re-classification of costs and/or segments that muddied the performance (is the company trying to hide something?). There are other items to consider in evaluating the quality of earnings—including assessing depreciation methods and other more fraudulent activity that can impact reported net income such as creating fictitious revenue and/or failing to record expenses—but for the most part, the five reasons outlined above cover the topic quite well in practice. Big Blue Became the Poster Child for Poor Earnings Quality Never did we ever think we’d be using Big Blue (IBM) as an example of poor earnings quality, but let's discuss the firm's historical results to get a feel for how poor earnings quality can translate into disappointing share-price performance. Shares of IBM once traded for more than $200 each prior to the collapse in the middle of last decade. Let's get started with the analysis. In IBM’s fourth-quarter 2013 income statement shown below, we have encircled three items that stood out to us at the time.

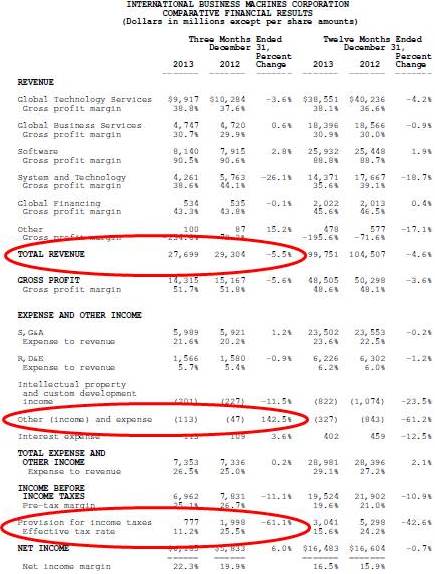

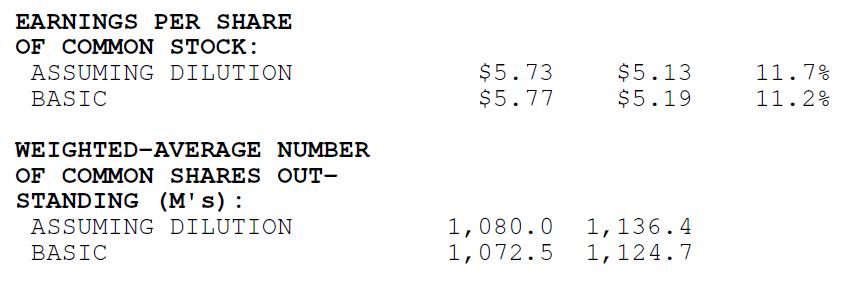

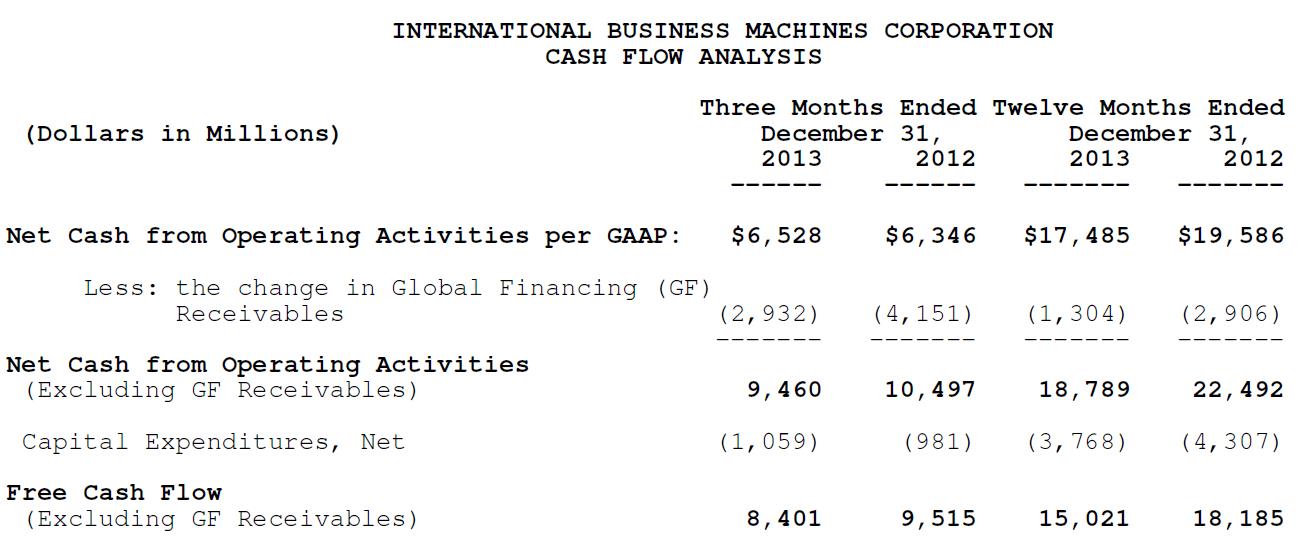

Image: IBM's earnings quality began to deteriorate significantly in 2013. Image Source: IBM The first is revenue growth. IBM’s fourth-quarter 2013 revenue dropped 5.5%, a pace that exceeded that of the 4.6% drop for the year, indicating an acceleration of the revenue decline. Without a solid backdrop of revenue growth, earnings-per-share expansion will have to come either from lower quality cost-cutting, one-time items, or share buybacks. Interestingly, IBM didn’t cut operating costs faster than the revenue declines in the period, as SG&A and RD&E as a percentage of revenue expanded, to 21.6% (up 140 basis points) and 5.7% (up 30 basis points), respectively. Clearly, revenue and costs had been moving in the wrong direction at IBM. However, IBM still reported a 6% increase in net income and a 240 basis point improvement in its net income margin for the quarter (see bottom two lines of the image above). Let’s examine how it did so by looking at the two other encircled items on its income statement. ‘Other (income) and expense’ advanced by $66 million—the measure is an offset to expenses, which is why it is a negative. Second, IBM’s tax rate (‘Effective tax rate’) tumbled significantly. Big Blue’s net income was more than $1 billion higher than it otherwise would have been (the ‘Provision for income taxes’ declined more than 60%). Given the declining revenue, increasing costs, and the one-time items that benefited the firm (other income and a lower tax rate), we view IBM’s earnings quality in the fourth quarter of 2013 as very poor. The quality of earnings expansion, however, was muddied even further. IBM bought back more than 50 million shares of stock (a reduction in share count to 1,072.5 million from 1,124.7 million), which further boosted headline earnings per share. On a diluted basis, IBM recorded ~11% earnings-per-share growth in the quarter, but there wasn’t anything fundamental in the quarter that should have driven such strong bottom-line expansion. Said differently, the buybacks contributed as an artificial means to hide weakening underlying fundamentals at the company.

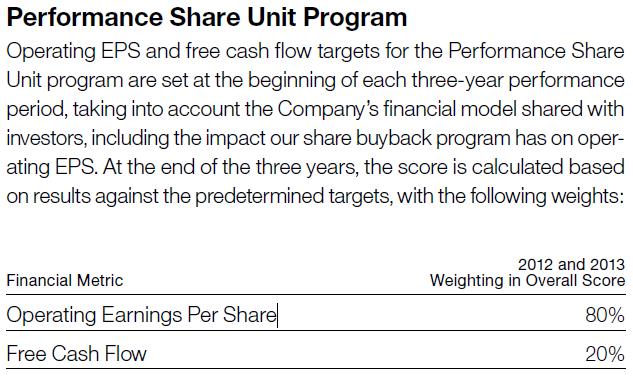

Image: IBM's buybacks were artificially boosting EPS. Image Source: IBM Another important consideration in assessing earnings quality is to ascertain whether cash flow from operations is increasing at a pace (or is at a level that is) consistent with net income expansion. If it isn’t, then the earnings the firm is posting on the income statement are more accounting-based than cash-flow based. For IBM, net cash from operations per GAAP is slightly higher than accounting earnings on the income statement (in the quarter and on an annual basis), so the possibility of any serious financial shenanigans at Big Blue was remote, in our view. On an annual basis, however, the decline in net cash from operating activities ($18.79 billion versus $22.49 billion) was much steeper than the fall in net income for the year ($16.5 billion versus $16.6 billion). Free cash flow trends weren’t that great either. As a percentage of net income, free cash flow fell to 91.1% in 2013 from 110% in 2012. The pace of the free cash flow decline was much steeper than that of net income on an annual basis.

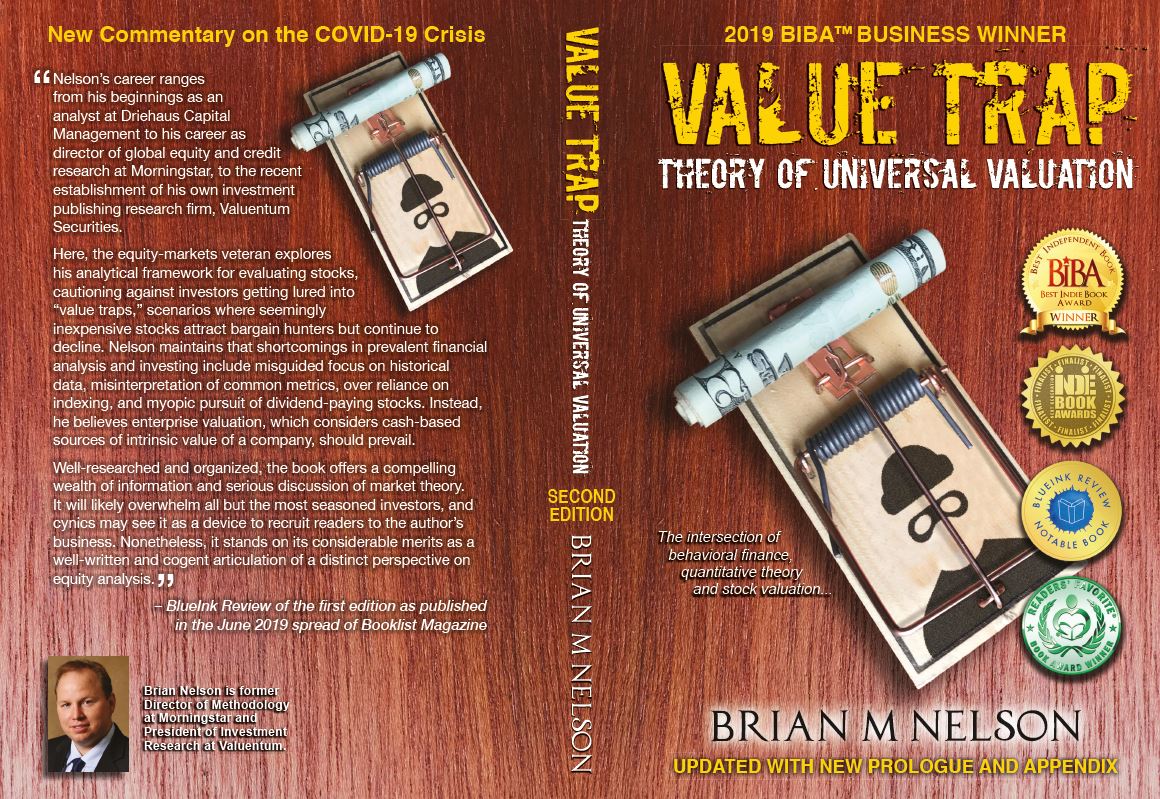

Image: It's paramount to pay attention to operating cash flow trends relative to net income. Image Source: IBM The steeper drop in cash flow (both operating cash flow and free cash flow) relative to the fall in net income shouldn’t be that surprising. A look at the breakdown in incentive compensation in IBM’s 2013 proxy statement, for example, revealed more of a focus on operating net income (60% weighting in executives’ annual incentive program) and operating earnings per share (an 80% weighting in executives’ performance share unit program) than anything else. [Please see page 34 of 2013 proxy statement here and/or image below.] As shareholders (owners of the company), they often get what they incentivize management to do.

Image: Incentives play an important role in outcomes. IBM had been incentivized more on driving operating earnings per share than on driving economic-value-added, ROIC dynamics. Such a focus on accounting EPS eventually led to low-quality earnings growth and eventually IBM's share-price weakness. Image Source: IBM Incentives based heavily on accounting EPS tend to do more harm than good, in our view. In this case, a strong case could be made that IBM's management "fell asleep at the wheel" by depending more on share buybacks to target operating earnings per share goals, instead of concentrating on tangible operating improvements to drive higher-quality ROIC. The result: After years of scraping by on poor earnings quality, IBM finally threw in the towel and ended up in late 2014 dropping its long-held operating earnings-per-share target for 2015 of $20 per share. The company's share buyback "buffer" was simply not enough to offset underlying business weakness and poor earnings quality--a situation that was not remedied by a management team, which was too busy focused on accounting EPS and not on economic-value-added dynamics. The stock suffered as a result. Valuentum’s Take on Earnings Quality As a matter of better corporate governance, we’d like to see a greater focus on return on invested capital (ROIC) and economic profit (EVA) than accounting measures. In addition to adding other ESG considerations to incentive programs, we think long-term performance will benefit from such a heightened focus. IBM didn’t engage in any large re-classifications to complicate year-over-year comparisons, but the firm’s quarterly results as outlined in this case study had flown in the face of what we and the Research Center for the CFA Institute characterize as high-quality earnings. The fourth quarter of 2013 at IBM was not (1) reflective of current operating performance, (2) a good indicator of future operating performance, and (3) helpful in assessing the intrinsic value of the company. As we look across our coverage universe today, perhaps Meta Platforms (META) may have become the new torch bearer of poor earnings quality as the social media giant deals with low earnings quality supported by aggressive layoffs in the wake of revenue pressure. NOW READ: Meta Platforms Surges Back to Fair Value Estimate ---------- It's Here!

The Second Edition of Value Trap! Order today!

-----

A version of this article appeared on our website January 22, 2014. Brian Nelson owns shares in SPY, SCHG, QQQ, DIA, VOT, BITO, RSP, and IWM. Valuentum owns SPY, SCHG, QQQ, VOO, and DIA. Brian Nelson's household owns shares in HON, DIS, HAS, NKE, DIA, and RSP. Some of the other securities written about in this article may be included in Valuentum's simulated newsletter portfolios. Contact Valuentum for more information about its editorial policies.

Valuentum members have access to our 16-page stock reports, Valuentum Buying Index ratings, Dividend Cushion ratios, fair value estimates and ranges, dividend reports and more. Not a member? Subscribe today. The first 14 days are free. |