As we arguably near the “peak” in the business cycle, labor is starting to demand more, a dynamic that we believe is emblematic of the period of aging economic expansion. Let’s have a look at what’s happening in the fight for higher wages.

By Brian Nelson, CFA

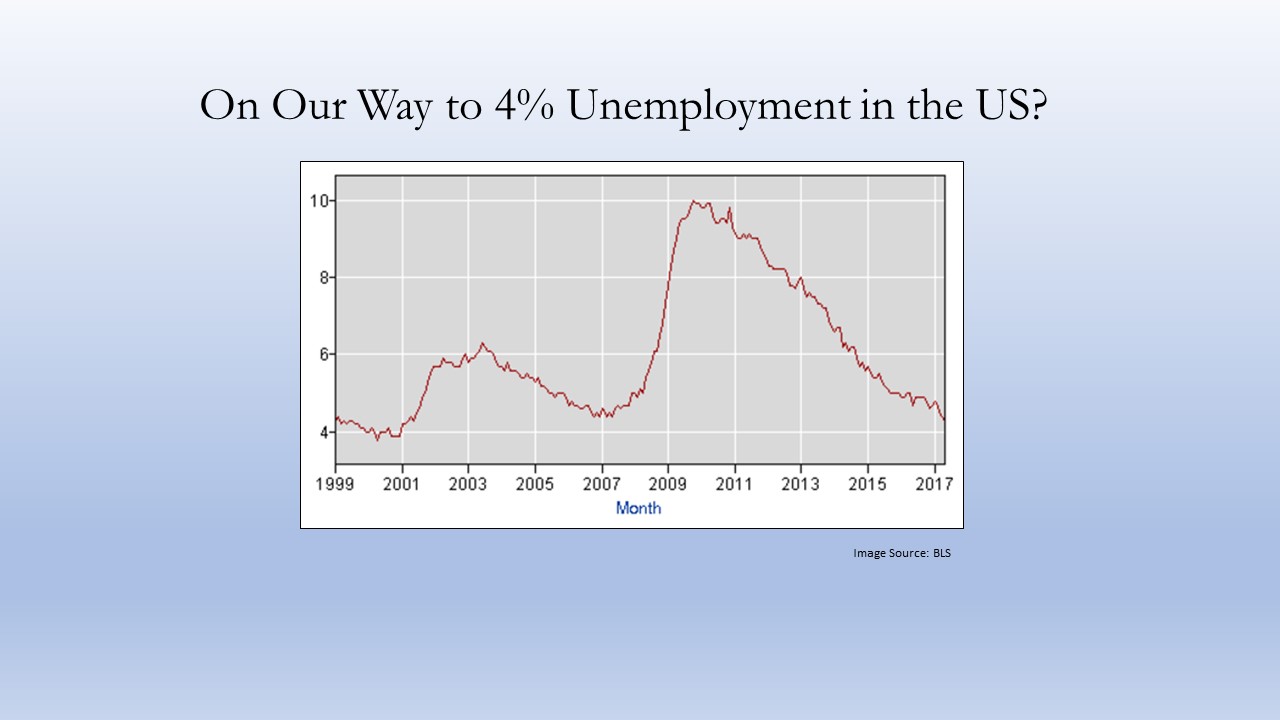

Each business cycle is different in both magnitude and duration, but there are some common qualities that define where an economy might be within the cycle. First, it has been more than 8 years since the March 2009 stock-market panic bottom, a period that witnessed firms such as Lehman Brothers, Bear Stearns, and AIG (AIG) flounder. The unemployment rate peaked at 10% during that difficult time.

Since then, the US economy has emerged from ‘recovery’ and has been in economic ‘expansion’ for several years, with absolute levels of gross domestic product now higher than the previous peak set before the Financial Crisis. During the third quarter of 2008, for example, the reading for US gross domestic product was $14.84 trillion. During the first quarter of 2017, the most recent data available, the reading for US gross domestic product was $19.03 trillion. You can view a graph of US gross domestic product here. The measure is the seasonally adjusted annual rate.

Today, we’re witnessing S&P 500 (SPY) companies generate tremendous profits, plow capital into buybacks at a solid pace, and increase dividends nicely, all the while the 10-year Treasury yield (TLT, TBT, TYO, TYD), a common benchmark for equity valuation and pricing debt, resides at 2.21%, as of June 1, near all-time lows. According to FactSet, for the first quarter of 2017, “the blended earnings growth rate for the S&P 500 is 14%,” marking “the highest (year-over-year) earnings growth rate for the index since the third quarter of 2011 (16.7%).” According to data from S&P compiled by Yardeni Research, the trailing four-quarter sum of buybacks and dividends paid reside near all-time highs. As of June 2017, US unemployment is now at 4.3%. Times are good, if not fantastic.

Though there may not be definitive analysis tying heightened wage pressure to the best of times and most readings that I have encountered are inconclusive, anecdotally, when times are good, workers often demand more. Intuitively, it makes sense. The #Fightfor15 movement has been around for some time now, but recent news is that it continues to gain momentum. The Wall Street Journal, for example, noted May 23 that the SEIU (Service International Union) is pushing for $15-an-hour pay for fast food workers in a bid to increase union membership. Restaurant companies that are less-franchised may pay a heavy burden if labor organizations are successful in the “Fight for 15,” but entities that have “franchised-out” their restaurants to business owners have effectively passed the potential for higher operating costs that would come from increased wages to the restauranteur.

This is important to understand. Capital-light, high-ROIC business models such as Domino’s (DPZ) and Dunkin’ Brands (DNKN), which are heavily-franchised–and even McDonald’s (MCD) now that it has stepped up its re-franchising efforts–are less exposed to rising wage rates (and labor costs) because such operating expenses don’t directly hit their P&L like that in a fully-owned operator (non-franchisor). Domino’s and Dunkin’ Brands’ customers, for example, are not necessarily the end consumers that buy the pizza and coffee, respectively, but instead they are the restauranteurs that pay the high-margin franchise fee to the corporation. By pursuing franchising or re-franchising initiatives, many restaurant holding-companies may be seeking to avoid the tail-risk of a step-change to labor costs, even if headlines speak to portfolio optimization and margin expansion initiatives.

Other highly-franchised entities include Papa John’s (PZZA)–where roughly 80% of its units in North America are franchised, and more than 95% of its roughly 1,650 international units are franchised–drive-in operator Sonic (SONC), which boasts a system that is ~90% franchised, and Wendy’s (WEN), which completed its goals to reduce its company-operated restaurant ownership to ~5% of its portfolio in 2016. DineEquity (DIN) is another mostly-franchised example, but the IHOP/Applebee’s concept owner continues to face considerable same-store sales pressure across its system, which we believe is an offsetting variable to any benefit accrued from an asset-light business model somewhat shielded from rising labor costs. Applebee’s domestic system-wide comparable same-restaurant sales, for example, fell nearly 8% in the first quarter of 2017.

Restaurants, on the other hand, that own (not franchise) most of their units such as Chipotle (CMG) or Cracker Barrel (CBRL), for example, may be more heavily exposed to rising minimum wage and union organization within the rank and file, as increased labor costs directly hit their P&Ls. None of Chipotle’s or Cracker Barrel’s restaurants are franchised. Roughly half of Starbucks’ (SBUX) 25,000+ stores are company-owned, and nearly 85% of Texas Roadhouse’s (TXRH) restaurants are company-owned. A little less than half of Buffalo Wild Wings’ (BWLD) restaurants are franchised, as of the end of the first quarter of 2017, but investors in B-dubs may have a lot more on their minds than the potential for rising labor costs. Executive turnover and the goings-on with Mercato Capital continue to make headlines. We still like the Buffalo Wild Wings concept, and we think the company has a variety of options to continue to generate shareholder value, “Buffalo Wild Wings: It’s Time to Start Delivering?”

That we continue to include Cracker Barrel as an idea in the Dividend Growth Newsletter portfolio suggests that, while we are watching labor developments, we’re not panicking. Our case for owning Cracker Barrel’s shares remains strong, “Cracker Barrel Hits the Trifecta,” and we think the restaurant’s demonstrated pricing strength will help mitigate the threat of rising labor costs that loom. Outside of the restaurant space, we think the fight for higher minimum wage will also have implications on large big box employers such as Walmart (WMT), Target (TGT) and Best Buy (BBY), even if it may be less-so for entities such as Costco (COST) that may already have higher wage structures. Walmart’s and Best Buy’s business models continue to be resilient in the face of Amazon, while Target’s faces a variety of challenges that we argue it brought upon itself, “…Target Is Still Suffering.”

We’ve also noticed some other activities by labor that we think are worthy of your attention. In April, the Writers Guild of America (WGA) authorized a strike, but cooler heads prevailed and in late May, the guild unanimously ratified a new contract. According to Variety, the strike in 2007 cost writers $285+ million in compensation and impacted programming, so a repeat would have had implications across our media coverage. Back in April 2016, more than 40,000 Verizon (VZ) workers went on strike, and AT&T (T) recently had to deal with a three-day walk-out by some 35,000 workers in mid-May 2017. Chicago Bridge and Iron (CBI) has been navigating an environment that has been “negatively impacted by underperformance on two union construction projects.” In late November 2016, hundreds of workers at Chicago O’Hare International Airport went on strike. Though there’s no definitive evidence that the rising tide of labor may ultimately signal the coming peak of economic expansion, we continue to be mindful of labor developments and their impact on the profit profiles of companies in our coverage universe.

The United States may very well be on its way to 4% unemployment, and while that sounds good, it may also spell the beginning of the end for the current phase of economic expansion. The “Fight for 15” continues.